Creating an Application

If you followed the installation guide and verified your setup you are ready to start building. This page walks you through writing a minimal VGLX application and assembling a simple world from a few core pieces. The example is small on purpose. It introduces the fundamentals without burying you in details.

By the end you’ll have a working application and a clear sense of how the engine fits together, enough to start exploring on your own.

Creating a Project

VGLX works best with CMake. In this section we create a small project so it can build cleanly on all platforms. To keep things simple we use a flat directory with just two files:

/hello-vglx

├── CMakeLists.txt

└── main.cppCMakeLists.txt holds a small build configuration:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.20)

project(hello-vglx)

set(CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD 23)

set(CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD_REQUIRED ON)

add_executable(hello-vglx main.cpp)

find_package(vglx REQUIRED)

target_link_libraries(hello-vglx PRIVATE vglx::vglx)

if (WIN32)

add_custom_command(TARGET hello-vglx POST_BUILD

COMMAND ${CMAKE_COMMAND} -E copy_if_different

$<TARGET_FILE:vglx::vglx>

$<TARGET_FILE_DIR:hello-vglx>

)

endif()The file starts by declaring the minimum CMake version, the project name and the language standard. We then create an executable and give it a single source file.

If you followed the installation guide you can import VGLX with two commands. find_package(vglx REQUIRED) asks CMake to locate the library. If it is missing or incorrectly installed, configuration fails. target_link_libraries links our application to the VGLX binaries.

The Windows-only section copies the VGLX DLL next to the executable after the build step. CMake selects the correct binary automatically based on your build type. Without this the application may fail to compile on Window unless you add the binaries to your system path.

This setup looks simple but CMake is doing a lot behind the scenes. It verifies the installation, loads the correct configuration and handles platform-specific details for us.

Before we move on, let’s add a minimal main.cpp to test that the project builds correctly:

#include <print>

#include <vglx/vglx.hpp>

auto main() -> int {

std::println("hello, world");

return 0;

}With both files in place you can configure and build the project from the project root:

cmake -S . -B build -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Debug

cmake --build build --config DebugAfter the build completes you should see the executable in the build directory.

- Linux/macOS:

build/hello-vglx - Windows:

build/Debug/hello-vglx.exe

Run it and you should be greeted by your application.

If CMake reports that it cannot find VGLX return to the installation guide and verify that the library was installed to a prefix CMake can locate. Otherwise you are ready to move on to the application entrypoint.

Application Runtime

The preferred way to create a VGLX application is using the application runtime. The runtime sets up the window, the rendering context, the main loop, and calls your hooks. You create a runtime instance by subclassing the Application class.

We can add a runtime instance to our bare-bones main.cpp file:

#include <vglx/vglx.hpp>

#include <memory>

struct MyApp : public vglx::Application {

auto Configure() -> Application::Parameters override {

return {

.title = "Hello VGLX",

.clear_color = {0x000000},

.width = 1280,

.height = 720,

.antialiasing = 4,

.vsync = false,

.show_stats = true,

};

}

auto CreateScene() -> std::unique_ptr<vglx::Scene> override {

return vglx::Scene::Create();

}

auto Update([[maybe_unused]] float dt) -> bool override {

return true;

}

};

auto main() -> int {

auto app = MyApp {};

app.Start();

return 0;

}Our class overrides three functions that initialize the runtime. Configure is optional but you will often implement it. It returns a small data object that describes how the application should start up. Using designated initializers keeps each field clear and easy to read.

CreateScene is required and returns the scene you want to render. At this stage we simply return an empty scene using its factory. VGLX uses unique pointers to manage nodes in the scene graph. The scene graph owns all nodes for their entire lifetime and built-in node types provide Create helpers to construct them correctly.

The last function, Update, is also required. It is called once per frame and is where you add per-frame logic at the application level. Returning true keeps the application running. Returning false exits the main loop.

In main we create an instance of the app and call Start to launch it. If you build and run the project again you should see a window for your new VGLX application.

Creating a Scene

Before you can put anything in your world you need a Scene. The scene is the root of your graph: every node hangs from it, inherits its state, and contributes to the final frame. It’s the anchor that ties cameras, lights, and geometry into a coherent world the renderer can walk.

In the earlier example we returned an empty scene. You can attach nodes directly to that instance but it’s often cleaner to subclass Scene. A custom scene gives you access to lifecycle hooks without cluttering the graph.

Add the following class definition above MyApp:

struct MyScene : public vglx::Scene {

MyScene() {}

auto OnAttached(vglx::SharedContextPointer context) -> void override {}

auto OnUpdate(float delta) -> void override {}

};This defines a MyScene type with an empty constructor and two hooks: OnAttached, called when the scene enters the runtime, and OnUpdate, called once per frame. We’ll fill these in shortly. First, tell the runtime to use MyScene:

auto CreateScene() -> std::unique_ptr<vglx::Scene> override {

return std::make_unique<MyScene>();

}Build and run the application again. If you still see an empty window, everything is working as intended. Now we can start putting things on screen.

Populating the Scene

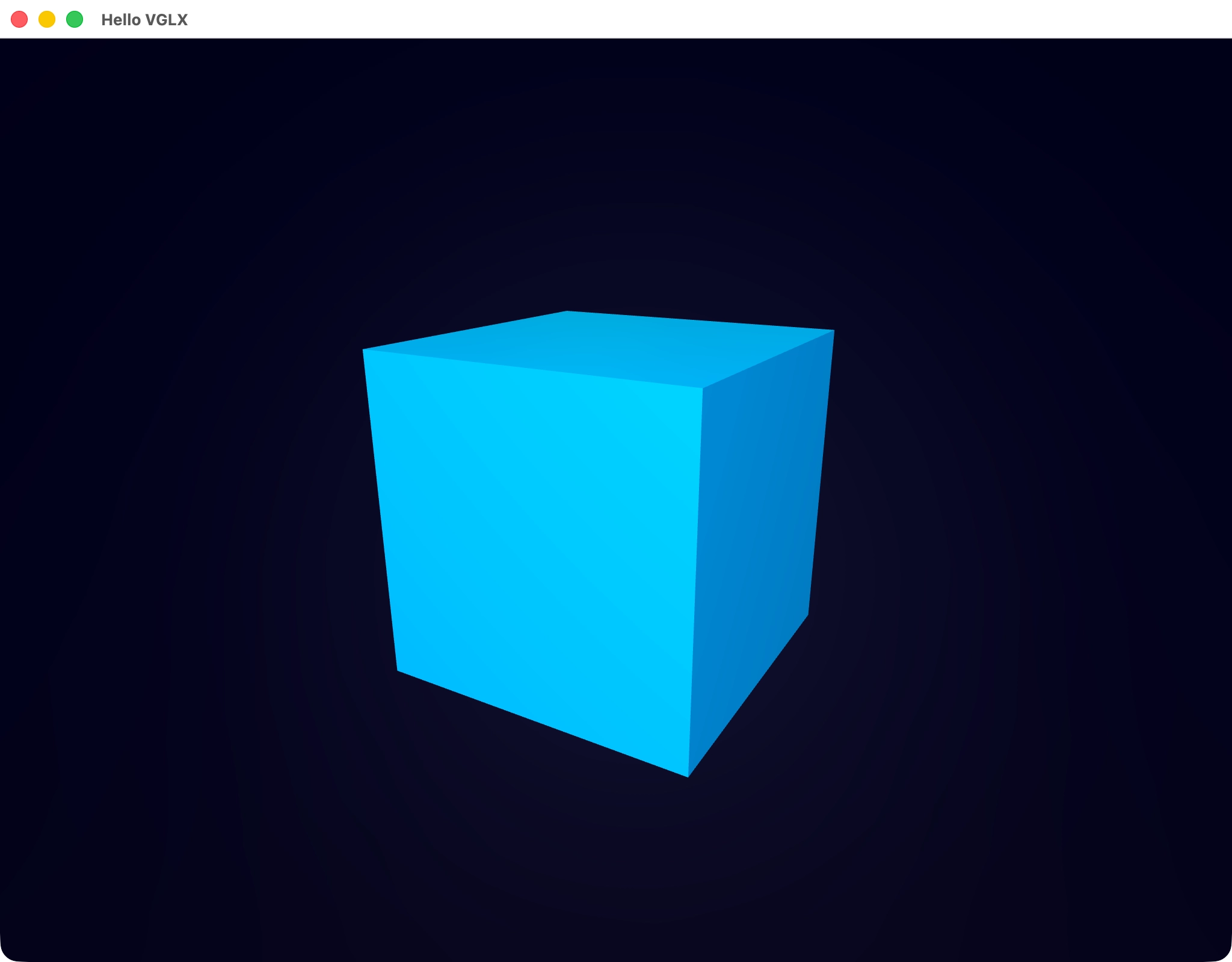

In this guide we’ll build a small scene: a 3D cube, a couple of lights, and a simple animation to make things interesting.

A scene is built from nodes: cameras, meshes, lights, and anything else you place in the world. To see anything on screen you need at least one of each and VGLX provides simple helpers to create and configure them. We’ll start with the camera.

The runtime gives you a default 3D camera unless you override CreateCamera so we’ll use that for now. By default the camera starts at the world origin . We want our cube to sit at the origin, not the camera, so we need to push the camera back and have it look toward the center of the scene.

Once a node is attached to the graph it can access the active camera through the shared context passed to OnAttached:

struct MyScene : public vglx::Scene {

MyScene() {}

auto OnAttached(vglx::SharedContextPointer context) -> void override {

context->camera->TranslateZ(2.5f); // push the camera back

}

auto OnUpdate(float delta) -> void override {}

};VGLX uses a right-handed coordinate system so moving the camera along +Z pushes it back toward the viewer while leaving the origin in front of it. With the camera in place we can add something to look at.

To render anything we need a renderable node. The most common one is a Mesh. A mesh combines two pieces: a Geometry which defines what to draw and a Material which defines how it should be drawn.

For a simple cube we can use the built-in BoxGeometry primitive, and because we want lighting in the scene we’ll pair it with a PhongMaterial:

struct MyScene : public vglx::Scene {

vglx::Mesh* mesh {nullptr};

MyScene() {

mesh = Add(vglx::Mesh::Create(

vglx::BoxGeometry::Create(),

vglx::PhongMaterial::Create(0x049EF4)

));

}

auto OnAttached(vglx::SharedContextPointer context) -> void override {

context->camera->TranslateZ(2.5f);

}

auto OnUpdate(float delta) -> void override {}

};Note that Mesh::Create returns a std::unique_ptr that is transferred to and owned by the scene graph. Calling Add returns a non-owning raw pointer which you may store and use for convenience. This pointer remains valid only while the node is attached to the scene graph; once the node is removed, the reference must no longer be used.

If we ran the application now we still wouldn’t see anything because the scene has no light sources. For this demo we’ll add two: an AmbientLight which illuminates everything uniformly from all directions, and a PointLight which represents a light source at a specific position that emits light in all directions like a small bulb.

We can add and configure both lights in our scene’s constructor:

MyScene() {

Add(vglx::AmbientLight::Create({

.color = 0xFFFFFF,

.intensity = 0.5f

}));

Add(vglx::PointLight::Create({

.color = 0xFFFFFF,

.intensity = 1.0f

}))->transform.Translate({2.0f, 2.5f, 4.0f});

mesh = Add(vglx::Mesh::Create(

vglx::BoxGeometry::Create(),

vglx::PhongMaterial::Create(0x049EF4)

));

}Both light sources need a color and an intensity. Unlike the ambient light, the point light is positional so we move it slightly up, to the right, and back to give the scene some depth.

If you run the application now you should see a blue square in the center of the window. That’s the front face of the cube viewed straight on.

Next we’ll animate it so the 3D shape becomes obvious.

Basic Animation

To keep things simple we’ll animate the scene by rotating the cube around the X and Y axes. All animation in VGLX happens inside a node’s update hook. In our case that’s the scene’s OnUpdate function, which is called once per frame.

auto OnUpdate(float delta) -> void override {

const auto rotation_speed = vglx::math::pi_over_2;

mesh->RotateX(rotation_speed * delta);

mesh->RotateY(rotation_speed * delta);

}The delta parameter represents the time, in seconds, since the previous frame. By scaling the rotation by delta the animation becomes time-based rather than frame-based. This ensures the cube rotates at the same speed regardless of frame rate.

If you run the application now, the square becomes a rotating cube, making the 3D nature of the scene clear.

Conclusion

In this guide we built a minimal VGLX application from scratch. We created a project, set up the application runtime, defined a custom scene, and populated it with a mesh, lights, and a camera. Finally, we added a simple animation to bring the scene to life.

This small example touches most of the core concepts you’ll use in any VGLX project: the application lifecycle, the scene graph, renderable nodes, lighting, transforms, and per-frame updates.

From here you can start experimenting. Try adding more meshes, changing materials, or introducing different types of lights. When you’re ready to go further, take a look at camera controls, input handling, and custom materials in the reference documentation.

The complete source code for this example is shown below for reference:

#include <vglx/vglx.hpp>

#include <memory>

struct MyScene : public vglx::Scene {

vglx::Mesh* mesh {nullptr};

MyScene() {

Add(vglx::AmbientLight::Create({

.color = 0xFFFFFF,

.intensity = 0.5f

}));

Add(vglx::PointLight::Create({

.color = 0xFFFFFF,

.intensity = 1.0f

}))->transform.Translate({2.0f, 2.5f, 4.0f});

mesh = Add(vglx::Mesh::Create(

vglx::BoxGeometry::Create(),

vglx::PhongMaterial::Create(0x049EF4)

));

}

auto OnAttached(vglx::SharedContextPointer context) -> void override {

context->camera->TranslateZ(2.5f);

}

auto OnUpdate(float delta) -> void override {

const auto rotation_speed = vglx::math::pi_over_2;

mesh->RotateX(rotation_speed * delta);

mesh->RotateY(rotation_speed * delta);

}

};

struct MyApp : public vglx::Application {

auto Configure() -> Application::Parameters override {

return {

.title = "Hello VGLX",

.clear_color = {0x000000},

.width = 1280,

.height = 720,

.antialiasing = 4,

.vsync = false,

.show_stats = true,

};

}

auto CreateScene() -> std::unique_ptr<vglx::Scene> override {

return std::make_unique<MyScene>();

}

auto Update([[maybe_unused]] float dt) -> bool override {

return true;

}

};

auto main() -> int {

auto app = MyApp {};

app.Start();

return 0;

}